Guatemala

Safety

We will write more generally about safety later on, but for now let’s focus on Guatemala. We were a bit anxious there at first, having heard all those stories of lawlessness and rampant crime. Here is what the Government of Canada has to say to those planning a visit to the country:

Foreigners are often targets of robbery, carjacking, sexual assault and rape, and armed assaults [...] Avoid low-cost hotels with poor security. Avoid walking after dark. Do not openly display laptop computers, mobile phones, or other electronic devices at any time [...] Avoid travelling in public buses (city or “chicken buses”) at all costs. They are mechanically unsafe, drivers are often unlicensed, and armed robberies on board are common. Public buses are often targeted by gangs who hurl grenades or fire shots as a way of ensuring compliance [...] Never approach or photograph children and women, since many people in Guatemala fear that children are being kidnapped for adoption or for theft of vital organs.

View from Cerro de la Cruz, Antigua

View from Cerro de la Cruz, Antigua

Sorry, Government of Canada, perhaps your intentions are good, but this description is complete and utter nonsense - not to mention an insult to the people of Guatemala. Certainly there is plenty of poverty, and in parts of the capital violent crime and gangland murders are part of the daily routine. But despite the ongoing flood of foreign visitors, attacks on travellers are very rare - even, believe it or not, when these travellers crisscross the country by chicken bus, flashing their fancy iPhones and getting all chummy with the village kids.

Here is an attempt to draft a more practical, less hysterical “travel advisory” for Guatemala:

- Just go. The people are beautiful, friendly, and welcoming. The culture and scenery are world-class, and the prices are laughable.

- Trust your instincts. If you’re uneasy about being somewhere, go someplace else.

- Stay in touch with your surroundings. Talk to fellow travellers. Talk to shop owners. Smile and say hello to the people you meet. When you’re part of the community, it becomes everybody’s job to keep you out of trouble.

- Eliminate 95% of problems by minimizing exposure to drunken crowds and deserted streets. If local children are out in the street, then presumably their parents think it is safe.

- Carry little cash and only those documents that you actually need. If you’re ever confronted, just hand them over - cash and documents are renewable resources.

La Merced, Antigua

La Merced, Antigua

Fashion

We won’t bore you with flowery descriptions of traditional Mayan dress. If interested, try the Footprint guidebook - it makes a point of explaining the traditional garb of every village in detail. We were rather more intrigued by contemporary Guatemalan fashion. Boys hold their hair up with enough gel to support the weight of a small refrigerator. New clothing is dominated by those cookie-cutter designs from Hollister and A&F that we’re all too used to seeing on campus in Vancouver. Then there are the so-called “American and European clothing” shops: these are your typical second-hand clothing stores, until you arrive at the T-shirt section. There, every forgotten corporate slogan, community function, and varsity sports team can get a new lease on life. Browse the inventory and be filled with voyeuristic joy as you flip through swag from long-forgotten championship runs by the Fighting Poodles of Lower Glaucoma county, advertisements for Moe’s auto body and muffler repair in St. Paul, and staff uniforms from Paradise golf resort and retirement home in Maui.

"The sky was the limit... at Lauren's Bat Mitzvah!"

"The sky was the limit... at Lauren's Bat Mitzvah!"

Finding good souvenir T-shirts to bring home has so far been difficult. The entertainment value of any particular “American clothing” shirt is limited once it is taken off the rack; the standard tourist fare is usually stupid and always overpriced; and we’re somewhat too old to serve as walking advertisements for Abercrombie and Fitch. The bottom line is, T-shirts just aren’t as much of a cultural icon in Central America as they are in other places.

A Trip to Mickey D’s

Now that's what I call a happy meal

Now that's what I call a happy meal

A visit to McDonald’s normally isn’t on the itinerary when we travel, but the branch in Antigua is really worth a look. It spans a very pretty McCourtyard, with a fountain in the centre and the massive bulk of volcan Agua in the background. There is also a large McInternet cafe. From the menu, in addition to the usual staples, you can order bottles of McWater, or upgrade your fries to McPatatas - quite good potato wedges which, for some crazy reason, are not available in North America.

What does a third-world country look like?

If we could definitively answer that question, we’d write the Nobel foundation and demand that they hand over the prize for our contribution to economics. Instead, here are a few observations about Guatemala, and how things work there:

Semuc Champey

Semuc Champey

- It certainly isn’t uniformly poor. Like everywhere else there is a small rich elite, but there is also a middle class, the working poor, the whole gamut. The economic structure in Guatemala is not as different from the West as one might think.

- All modern products and services are available, but coverage can be patchy. This applies to everything from healthcare and roads to camping gear and imported delicacies. Mobile phone coverage is the exception: every dusty country road in Guatemala has cell coverage, including mobile internet.

- A very lax approach to business (or absence of greed, depending on your viewpoint). My little shop or guesthouse is doing well? Rather than reinvest the profits in expansion or improvement, let’s allow the place to deteriorate a bit, and see if people still come.

- Schooling for children in rural areas lasts for 3-5 years, and even then many of them will have to work in the morning before going to school in the afternoon. One in three rural Guatemalans never learns to read.

- Hordes of well-intentioned foreigners, with all sorts of motivations, running every imaginable community development project from organic agriculture to musical therapy. Some travellers pay a lot of money for the privilege of volunteering in Guatemala. Who these projects are ultimately helping is a question beyond the scope of this blog.

Fun times in Semuc Champey

Fun times in Semuc Champey

What do backpackers look like?

We’d like to think that we look like backpackers, especially now that parts of our gear are starting to fall apart and bits of duct tape adorn shoes, clothes, packs, and glasses. Backpackers come in all ages and sizes, and while we’re above the median age, we are by no means an outlier. What mystifies us about the backpacker population is why they are so often tattooed, pierced in strange places, and continuously drawing on their cigarettes (tobacco, unfortunately; it wouldn’t smell as vile if it were pot).

What else? Americans and Canadians are naturally the most dominant groups. The other usual suspects are all represented: Germans and Swiss, Australians and Kiwis, Israelis, Britons, Scandinavians. In addition, there’s a substantial population of Latin Americans on the trail. Travelling with your Macbook by now seems to be completely acceptable (to most people). Work-travel arrangements are far less common in Central America than in richer countries, but many travellers take time to learn the language and/or do volunteer work.

Preparing to gobble up our Aussie burgers, Rio Dulce

Preparing to gobble up our Aussie burgers, Rio Dulce

Pacaya

Pacaya volcano is quite a sight - or was, until 2010. Lava flows were pretty much continuous, making Pacaya a must-do day trip. Then in May of 2010 the mountain exploded in its biggest eruption to date. Neighbouring villagers, having no time to evacuate, hid under tables while pumice rained down on the countryside. Fortunately no one was killed, and Pacaya, having literally let out some steam, calmed down substantially afterwards. No more lava flows, no more volcanic ash. But the day trip remains as popular now as it was then.

Roasting marshmallows on Pacaya

Roasting marshmallows on Pacaya

Ron signed up for the trip alone while Dana was recovering from what we suspect was some tainted salad. The transfer from Antigua was populated by two middle-aged Britons and four Aussies. As soon as we arrived at the trailhead a very aggressive sales pitch began: a group of children bearing heavy wooden staffs swarmed us yelling “Stick sir! Stick! Need a stick?” But buying stuff from street children encourages truancy, and we all opted out.

While shaking off the kids was relatively easy, the cowboys were a lot more persistent. Six young men on horseback started following us up the trail, calling out “Taxi! Hos! Taxi sir!” Presumably, what happens in Pacaya is that many people show up not realizing that climbing a volcano involves some elevation gain (not a lot in this case, just a quick stroll compared to Santa Maria). None of our group took up the offer of the “taxi”, but the men had little else to do, so they followed us halfway up the trail before finally giving up. Hiking up with a pack of horses right on our heels was slightly unnerving and not altogether pleasant.

The only active volcanic feature remaining on Pacaya is a number of steam vents. As we parked by one such vent, our guide pulled out a huge bag of marshmallows and some long wooden skewers, and everyone proceeded to stuff themselves full of lava-roasted marshmallows, all the while professing their dislike of the taste (we’re adults after all, we’re not supposed to gorge ourselves with candy and call it dinner). On the way down we were treated to a dramatic display of lightning bolts attacking the peak of volcan Fuego - certainly more inspiring and less intimidating when watched from a safe distance away.

Lanquin

The pools at Semuc Champey, one of Guatemala’s most famous natural attractions, lie at the end of a very rough dirt road - eleven km and almost a full hour of bumpy riding past the village of Lanquin, which in turn can only be reached by another long section of dirt track. Considering its poor access, Lanquin is actually quite a big place. It is a regional centre for the surrounding villages, and even has two restaurants.

El Retiro lodge, Lanquin

El Retiro lodge, Lanquin

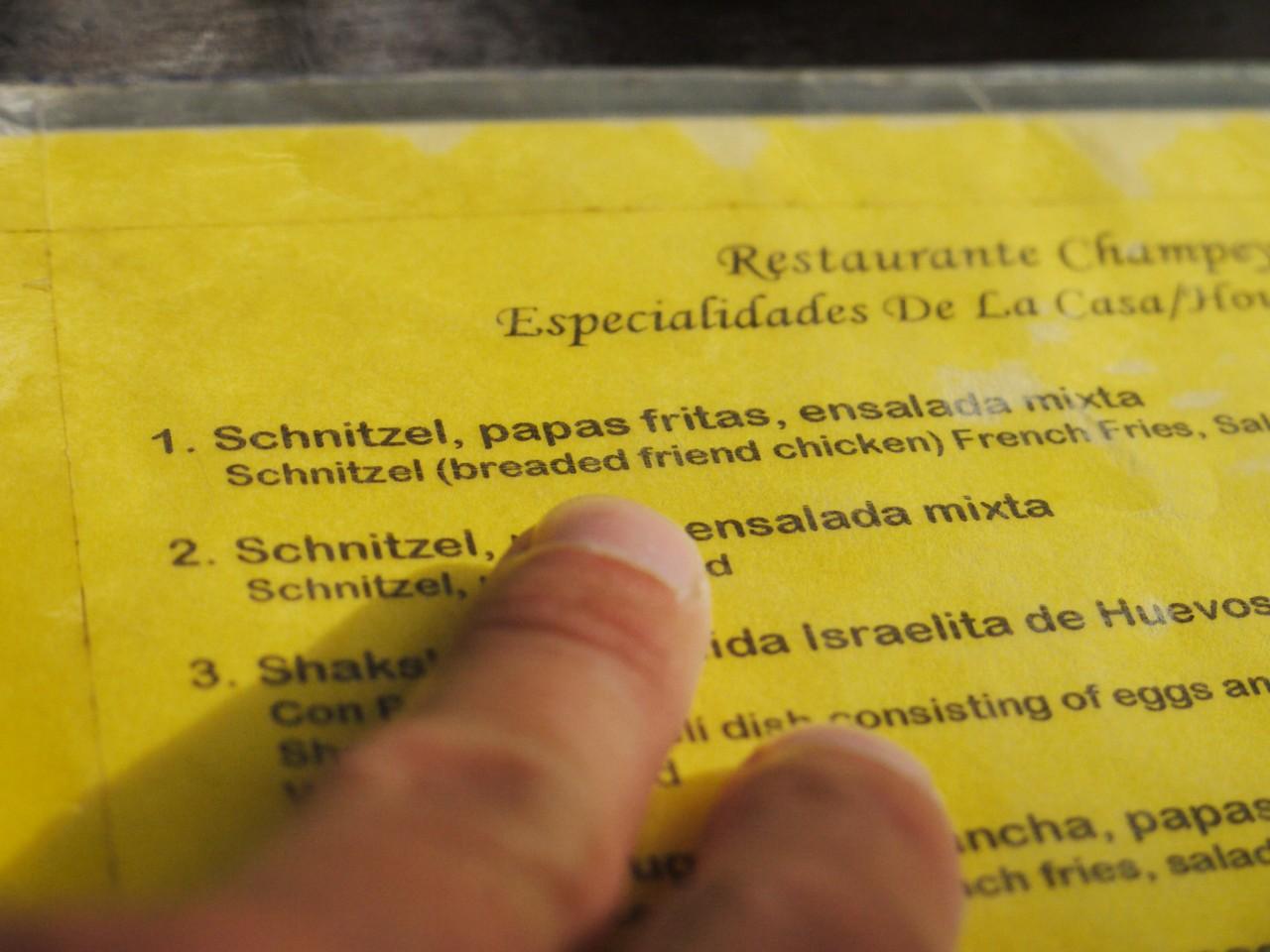

Guatemalan cuisine is quite different from the Mexican, although corn tortillas and beans feature heavily in both. Many dishes are fried: fried chicken, fried plantain, potato fries, fried desserts, fried eggs. Plenty of eggs. And tomatoes. And bread. The food here turns out to be close enough to Israeli home cooking that, once the backpackers started arriving, some of their dishes were adopted locally: shakshuka (eggs and tomatoes), chicken schnitzel, and falafel are all prepared in restaurants and homes.

Lanquin sees enough Hebrew-speaking traffic that the language is spreading, too. Hostel workers and guides would greet us in broken Hebrew and we would respond in broken Spanish, making both parties happy. Usually the conversation would revert to English if any complex ideas had to be conveyed. The native language here is Qeq’chi’, which sounds a bit like Hebrew although the two have no relation whatsoever.

Guatemalan-Israeli fusion menu, Lanquin

Guatemalan-Israeli fusion menu, Lanquin

Guatemata

From Lanquin we took a shuttle to Rio Dulce, jumping and rattling along a road advertised as the “direct ecological route” to the Caribbean. Like most everything in Guatemala, the tourist shuttles are a bit of a hack: they are sold as a transfer service, and priced accordingly, but ultimately it’s just a guy in a minivan going from A to B (often through C and D) and running whatever errands need to be run - picking up locals for short-haul lifts, delivering groceries, and so on. Any estimate of trip duration should be incremented by two hours and taken with a grain of salt. Our journey included a delivery of eggs to a mining facility, ferrying kids home from school, and a brief reunion with the driver’s nephews in one of the villages. Eventually we descended into the lowland region that Ron insists on calling Guatemata (since “mala” means “upward” in Hebrew, and “mata” is downward), where maize plantations and roaming chickens and pigs are abruptly replaced by cattle ranches.

Kayaking on Rio Dulce

Kayaking on Rio Dulce

Rio Dulce is where the Guatemalan one-percenters build their vacation homes - not in the town itself, mind you, but on the shores of the river or in little inlets surrounded by lush tropical forest. We stayed in an Australian-run lodge called (somewhat unimaginatively) Hotel Kangaroo - a beautiful spot, built entirely on stilts and accessible only by boat. Their restaurant serves up some of the best Aussie “works” burgers to be found anywhere, let alone in Central America.

We later spent a few hours stranded in the town of Livingston, waiting for the boat to take us to Belize. Livingston seems to underwhelm most visitors, which is why we had decided not to stay there. Having seen it briefly, perhaps we should at least have spent the night. A Garifuna town (rather than Ladino or Maya), it looks and feels, and tastes and sounds, different from anywhere else in Guatemala. We will add it to the “to do” pile for next time.

Tapado, a traditional Garifuna soup, Livingston

Tapado, a traditional Garifuna soup, Livingston

More photos from Guatemala here.

Next report: old memories and new adventures in a strange little nation.